Chapter 10. The Far East to World War I

THE COLLAPSE OF CHINA TO 1920

The destruction of traditional Chinese culture under the impact of Western Civilization was considerably later than the similar destruction of Indian culture by Europeans. This delay arose from the fact that European pressure on India was applied fairly steadily from the early sixteenth century, while in the Far East, in Japan even more completely than in China, this pressure was relaxed from the early seventeenth century for almost two hundred years, to 1794 in the case of China and to 1854 in the case of Japan. As a result, we can see the process by which European culture was able to destroy the traditional native cultures of Asia more clearly in China than almost anywhere else.

The traditional culture of China, as elsewhere in Asia, consisted of a military and bureaucratic hierarchy superimposed on a great mass of hardworking peasantry. It is customary, in studying this subject, to divide this hierarchy into three levels. Politically, these three levels consisted of the imperial authority at the top, an enormous hierarchy of imperial and provincial officials in the middle, and the myriad of semi-patriarchal, semi-democratic local villages at the bottom. Socially, this hierarchy was similarly divided into the ruling class, the gentry, and the peasants. And, economically, there was a parallel division, the uppermost group deriving its incomes as tribute and taxes from its possession of military and political power, while the middle group derived its incomes from economic sources, as interest on loans, rents from lands, and the profits of commercial enterprise, as well as from the salaries, graft, and other emoluments arising from his middle group's control of the bureaucracy. At the bottom the peasantry, which was the only really productive group in the society, derived its incomes from the sweat of its collective brows, and had to survive on what was left to it after a substantial fraction of its product had gone to the two higher groups in the form of rents, taxes, interest, customary bribes (called "squeeze"), and excessive profits on such purchased "necessities" of life as salt, iron, or opium.

Although the peasants were clearly an exploited group in the traditional society of China, this exploitation was impersonal and traditional and this more easily borne shall if it had been personal or arbitrary. In the course of time, a workable system of customary relationships had come into existence among the three levels of society. Each group knew its established relationships with the others, and used those relationships to avoid any sudden or excessive pressures which might disrupt the established patterns of the society. The political and military force of the imperial regime rarely impinged directly on the peasantry, since the bureaucracy intervened between them as a protecting buffer. This buffer followed a pattern of deliberate amorphous inefficiency so that the military and political force from above had been diffused, dispersed, and blunted by the time it reached down to the peasant villages. The bureaucracy followed this pattern because it recognized that the peasantry was the source of its incomes, and it had no desire to create such discontent as would jeopardize the productive process or the payments of rents, taxes, and interest on which it lived. Furthermore, the inefficiency of the system was both customary and deliberate, since it allowed a large portion of the wealth which was being drained from the peasantry to be diverted and diffused among the middle class of gentry before the remnants of it reached the imperial group at the top.

This imperial group, in its turn, had to accept this system of inefficiency and diversion of incomes and its own basic remoteness from the peasantry because of the great size of China, the ineffectiveness of its systems of transportation and communications, and the impossibility of keeping records of population, or of incomes and taxes except through the indirect mediation of the bureaucracy. The semi-autonomous position of the bureaucracy depended, to a considerable extent, on the fact that the Chinese system of writing was so cumbersome, so inefficient, and so difficult to learn that the central government could not possibly have kept any records or have administered tax collection, public order, or justice except through a bureaucracy of trained experts. This bureaucracy was recruited from the gentry because the complex systems of writing, of law, and of administrative traditions could be mastered only by a group possessing leisure based on unearned incomes. To be sure, in time, the training for this bureaucracy and for the examinations admitting to it became quite unrealistic, consisting largely of memorizing of ancient literary texts for examination purposes rather than for any cultural or administrative ends. This was not so bad as it sounds, for many of the memorized texts contained a good deal of ancient wisdom with an ethical or practical slant, and the possession of this store of knowledge engendered in its possessors a respect for moderation and for tradition which was just what the system required. No one regretted that the system of education and of examinations leading to the bureaucracy did not engender a thirst for efficiency, because efficiency was not a quality which anyone desired. The bureaucracy itself did not desire efficiency because this would have reduced its ability to divert the funds flowing upward from the peasantry.

The peasantry surely did not want any increase in efficiency, which would have led to an increase in pressure on it and would have made it less easy to blunt or to avoid the impact of imperial power. The imperial power itself had little desire for any increased efficiency in its bureaucracy, since this might have led to increased independence on the part of the bureaucracy. So long as the imperial superstructure of Chinese society obtained its share of the wealth flowing upward from the peasantry, it was satisfied. The share of this wealth which the imperial group obtained was very large, in absolute figures, although proportionately it was only a small part of the total amount which left the peasant class, the larger part being diverted by the gentry and bureaucracy on its upward flow.

The exploitative nature of this three-class social system was alleviated, as we have seen, by inefficiency, by traditional moderation and accepted ethical ideas, by a sense of social interdependence, and by the power of traditional law and custom which protected the ordinary peasant from arbitrary treatment or the direct impact of force. Most important of all, perhaps, the system was alleviated by the existence of careers open to talent. China never became organized into hereditary groups or castes, being in this respect like England and quite unlike India. The way was open to the top in Chinese society, not for any individual peasant in his own lifetime, but to any individual peasant family over a period of several generations. Thus an individual's position in society depended, not on the efforts of his own youth, but on the efforts of his father and grandfather.

If a Chinese peasant was diligent, shrewd, and lucky, he could expect to accumulate some small surplus beyond the subsistence of his own family and the drain to the upper classes. This surplus could be invested in activities such as iron-making, opium selling, lumber or fuel selling, pig-trading and such. The profits from these activities could then be invested in small bits of land to be rented out to less fortunate peasants or in loans to other peasants. If times remained good, the owner of the surpluses began to receive rents and interest from his neighbors; if times became bad he still had his land or could take over his debtor's land as forfeited collateral on his loan. In good times or bad, the growth of population in China kept the demand for land high, and peasants were able to rise in the social scale from peasantry to gentry by slowly expanding their legal claims over land. Once in the gentry, one's children or grandchildren could be educated to pass the bureaucratic examinations and be admitted to the group of mandarins. A family which had a member or two in this group gained access to the whole system of "squeeze" and of bureaucratic diversion of income flows, so that the family as a whole could continue to rise in the social and economic structure. Eventually some member of the family might move into the imperial center from the provincial level on which this rise began, and might even gain access to the imperial ruling group itself.

In these higher levels of the social structure many families were able to maintain a position for generations, but in general there was a steady, if slow, "circulation of the elite," most families remaining in a high social position for only a couple of generations, after about three generations of climb, to be followed by a couple of generations of decline. Thus, the old American saying that it took only three generations "from shirt-sleeves to shirt-sleeves" would, in the old China, have to be extended to allow about six or seven generations from the rice paddy's drudgery back to the rice paddy again. But the hope of such a rise contributed much to increase individual diligence and family solidarity and to reduce peasant discontent. Only in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century did peasants in China come to regard their positions as so hopeless that violence became preferable to diligence or conformity. This change arose from the fact, as we shall see, that the impact of Western culture on China did, in fact, make the peasant’s position economically hopeless.

In traditional Chinese society the bureaucrats recruited through examinations from the gentry class were called mandarins. They became, for all practical purposes, the dominant element in Chinese society. Since their social and economic position did not rest on political or military power but on traditions, the legal structure, social stability, accepted ethical teachings, and the rights of property, this middle-level group gave Chinese society a powerful traditionalist orientation. Respect for old traditions, for the accepted modes of thought and action, for the ancestors in society and religion, and for the father in the family became the salient characteristics of Chinese society. That this society was a complex network of vested interests, was unprogressive, and was shot through with corruption was no more objectionable to the average Chinese, on any level, than the fact that it was also shot through with inefficiency.

These things became objectionable only when Chinese society came directly in contact with European culture during the nineteenth century. As these two societies collided, inefficiency, unprogressiveness, corruption, and the whole nexus of vested interests and traditions which constituted Chinese society was unable to survive in contact with the efficiency, the progressiveness, and the instruments of penetration and domination of Europeans. A system could not hope to survive which could not provide itself with firearms in large quantities or with mass armies of loyal soldiers to use such weapons, a system which could not increase its taxes or its output of wealth or which could not keep track of its own population or its own incomes by effective records or which had no effective methods of communication and transportation over an area of 3.5 million square miles.

The society of the West which began to impinge on China about 1800 was powerful, efficient, and progressive. It had no respect for the corruption, the traditions, the property rights, the family solidarity, or the ethical moderation of traditional Chinese society. As the weapons of the West, along with its efficient methods of sanitation, of writing, of transportation and communications, of individual self-interest, and of corrosive intellectual rationalism came into contact with Chinese society, they began to dissolve it. On the one hand, Chinese society was too weak to defend itself against the West. When it tried to do so, as in the Opium Wars and other struggles of 1841-1861, or in the Boxer uprising of 1900, such Chinese resistance to European penetration was crushed by the armaments of the Western Powers, and all kinds of concessions to these Powers were imposed on China.

Until 1841 Canton was the only port allowed for foreign imports, and opium was illegal. As a consequence of Chinese destruction of illegal Indian opium and the commercial exactions of Cantonese authorities, Britain imposed on China the treaties of Nanking (1842) and of Tientsin (1858). These forced China to cede Hong Kong to Britain and to open sixteen ports to foreign trade, to impose a uniform import tariff of no more than 5 percent, to pay an indemnity of about $100 million, to permit foreign legations in Peking, to allow a British official to act as head of the Chinese customs service, and to legalize the import of opium. Other agreements were imposed by which China lost various fringe areas such as Burma (to Britain), Indochina (to France), Formosa and the Pescadores (to Japan), and Macao (to Portugal), while other areas were taken on leases of various durations, from twenty-five to ninety-nine years. In this way Germany took Kiaochow, Russia took southern Liaotung (including Port Arthur), France took Kwangcho-wan, and Britain took Kowloon and Weihaiwei. In this same period various Powers imposed on China a system of extraterritorial courts under which foreigners, in judicial cases, could not be tried in Chinese courts or under Chinese law.

The political impact of Western civilization on China, great as it was, was overshadowed by the economic impact. We have already indicated that China was a largely agrarian country. Years of cultivation and the slow growth of population had given rise to a relentless pressure on the soil and to a destructive exploitation of its vegetative resources. .Most of the country was deforested, resulting in shortage of fuel, rapid runoff of precipitation, constant danger of floods, and large-scale erosion of the soil. Cultivation had been extended to remote valleys and up the slopes of hills by population pressures, with a great increase in the same destructive consequences, in spite of the fact that many slopes were rebuilt in terraces. The fact that the southern portion of the country depended on rice cultivation created many problems, since this crop, of relatively low nutritive value, required great expenditure of labor (transplanting and weeding) under conditions which were destructive of good health. Long periods of wading in rice paddies exposed most peasants to various kinds of joint diseases, and to water-borne infections such as malaria or parasitical flukes.

The pressure on the soil was intensified by the fact that 60 percent of China was over 6,000 feet above sea level, too high for cultivation, while more than half the land had inadequate rainfall (below twenty inches a year). Moreover, the rainfall was provided by the erratic monsoon winds which frequently brought floods and occasionally failed completely, causing wholesale famine. In the United States 140 million people were supported by the labor of 6.5 million farmers on 365 million acres of cultivated land in 1945; China, about the same time, had almost 500 million persons supported by the labor of 65 million farmers on only 217 million acres of cultivated land. In China the average farm was only a little over four acres (compared to 157 in the United States) but was divided into five or six separate fields and had, on the average, 6.2 persons living on it (compared to 4.2 persons on the immensely larger American farm). As a result, in China there was only about half an acre of land for each person living on the land, compared to the American figure of 15.7 acres per person.

As a consequence of this pressure on the land, the average Chinese peasant had, even in earlier times, no margin above the subsistence level, especially when we recall that a certain part of his income flowed upward to the upper classes. Since, on his agricultural account alone, the average Chinese peasant was below the subsistence level, he had to use various ingenious devices to get up to that level. All purchases of goods produced off the farm were kept at an absolute minimum. Every wisp of grass, fallen leaf, or crop residue was collected to serve as fuel. All human waste products, including those of the cities, were carefully collected and restored to the soil as fertilizer. For this reason, farmlands around cities, because of the greater supply of such wastes, were more productive than more remote farms which were dependent on local supplies of such human wastes. Collection and sale of such wastes became an important link in the agricultural economics of China. Since the human digestive system extracts only part of the nutritive elements in food, the remaining elements were frequently extracted by feeding such wastes to swine, thus passing them through the pig's digestive system before these wastes returned to the soil to provide nourishment for new crops and, thus, for new food. Every peasant farm had at least one pig which was purchased young, lived in the farm latrine until it was full grown, and then was sold into the city to provide a cash margin for such necessary purchases as salt, sugar, oils, or iron products. In a somewhat similar way the rice paddy was able to contribute to the farmer's supply of proteins by acting as a fishpond and an aquarium for minute freshwater shrimp.

In China, as in Europe, the aims of agricultural efficiency were quite different from the aims of agricultural efficiency in new countries, such as the United States, Canada, Argentina, or Australia. In these newer countries there was a shortage of labor and a surplus of land, while in Europe and Asia there was a shortage of land and a surplus of labor. Accordingly, the aim of agricultural efficiency in newer lands was high output of crops per unit of labor. It was for this reason that American agriculture put such emphasis on labor-saving agricultural machinery and soil-exhausting agricultural practices, while Asiatic agriculture put immense amounts of hand labor on small amounts of land in order to save the soil and to win the maximum crop from the limited amount of land. In America the farmer could afford to spend large sums for farm machinery because the labor such machinery replaced would have been expensive anyway and because the cost of that machinery was spread over such a large acreage that its cost per acre was relatively moderate. In Asia there was no capital for such expenditures on machinery because there was no margin of surplus above subsistence in the hands of the peasantry and because the average farm was so small that the cost of machinery per acre (either to buy or even to operate) would have been prohibitive.

The only surplus in Asia was of labor, and every effort was made, by putting more and more labor on the land, to make the limited amount of land more productive. One result of this investment of labor in land in China can be seen in the fact that about half of the Chinese farm acreage was irrigated while about a quarter of it was terraced. Another result of this excess concentration of labor on land was that such labor was underemployed and semi-idle for about three-quarters of the year, being fully busy only in the planting and harvest seasons. From this semi-idleness of the Asiatic rural population came the most important effort to supplement peasant incomes through rural handicrafts. Before we turn to this crucial point, we should glance at the relative success of China's efforts to achieve high-unit yields in agriculture.

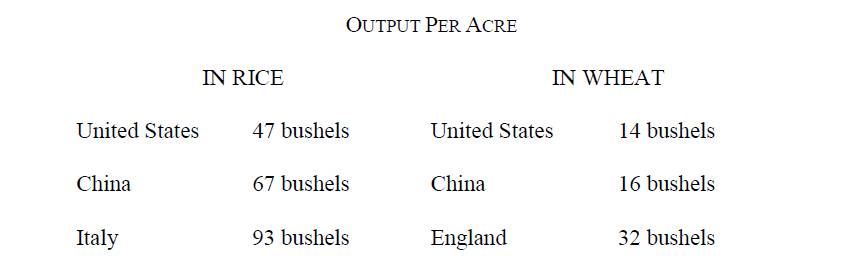

In the United States, about 1940, each acre of wheat required 1.2 man-days of work each year; in China an acre of wheat took 26 man-days of labor. The rewards of such expenditures of labor were quite different. In China the output of grain for each man-year of labor was 3,080 pounds; in the United States the output was 44,000 pounds per man-year of labor. This low productivity of agricultural labor in China would have been perfectly acceptable if China had, instead, achieved high output per acre. Unfortunately, even in this alternative aim China was only moderately successful, more successful than the United States, it is true, but far less successful than European countries which aimed at the same type of agricultural efficiency (high yields per acre) as China did. This can be seen from the following figures:

These figures indicate the relative failure of Chinese (and other Asiatic) agriculture even in terms of its own aims. This relative failure was not caused by lack of effort, but by such factors as (1) farms too small for efficient operation; (2) excessive population pressure which forced farming onto less productive soil and which drew more nutritive elements out of the soil than could be replaced, even by wholesale use of human wastes as fertilizer; ( 3) lack of such scientific agricultural techniques as seed selection or crop rotation; and (4) the erratic character of a monsoon climate on a deforested and semieroded land.

Because of the relatively low productivity of Chinese (and all Asiatic) agriculture, the whole population was close to the margin of subsistence and, at irregular intervals, was forced below that margin into widespread famine. In China the situation was alleviated to some extent by three forces. In the first place, the irregular famines which we have mentioned, and somewhat more frequent onslaughts of plague disease, kept the population within manageable bounds. These two irregular occurrences reduced the population by millions, in both China and India, when they occurred. Even in ordinary years the death rate was high, about 30 per thousand in China compared to 25 in India, 12.3 in England, or 8.7 in Australia. Infant mortality (in the first year of life) was about 159 per thousand in China compared to 240 in India, about 70 in western Europe, and about 32 in New Zealand. At birth an infant could be expected to live less than 27 years in India, less than 35 years in China, about 60 years in England or the United States, and about 66 years in New Zealand (all figures are about 1930). In spite of this "expectation of death" in China, the population was maintained at a high level by a birth rate of about 38 per thousand of the population compared to 34 in India, 18 in the United States or Australia, and 15 in England. The skyrocketing effect which the use of modern sanitary or medical practices might have upon China's population figures can be gathered from the fact that about three-quarters of Chinese deaths are from causes which are preventable (usually easily preventable) in the West. For example, a quarter of all deaths are from diseases spread by human wastes; about 10 percent come from childhood diseases like smallpox, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and whooping cough; about 15 percent arise from tuberculosis; and about 7 percent are in childbirth.

The birthrate was kept up, in traditional Chinese society as a consequence of a group of ideas which are usually known as "ancestor worship." Every Chinese family had, as its most powerful motivation, the conviction that the family line must be continued in order to have descendants to keep up the family shrines, to maintain the ancestral graves, and to support the living members of the family after their productive years had ended. The expense of such shrines, graves, and old persons was a considerable burden on the average Chinese family and a cumulative burden as well, since the diligence of earlier generations frequently left a family with shrines and graves so elaborate that upkeep alone was a heavy expense to later generations. At the same time the urge to have sons kept the birth rate up and led to such undesirable social practices, in traditional Chinese society, as infanticide, abandonment, or sale of female offspring. Another consequence of these ideas was that more well-to-do families in China tended to have more children than poor families. This was the exact opposite of the situation in Western civilization, where a rise in the economic scale resulted in the acquisition of a middle-class outlook which included restriction of the family's offspring.

The pressure of China's population on the level of subsistence was relieved to some extent by wholesale Chinese emigration in the period after 1800. This outward movement was toward the less settled areas of Manchuria, Mongolia, and southwestern China, overseas to America and Europe, and, above all, to the tropical areas of southeastern Asia (especially to Malaya and Indonesia). In these areas, the diligence, frugality, and shrewdness of the Chinese provided them with a good living and in some cases with considerable wealth. They generally acted as a commercial middle class pushing inward between the native Malaysian or Indonesian peasants and the upper group of ruling whites. This movement, which began centuries ago, steadily accelerated after 1900 and gave rise to unfavorable reactions from the non-Chinese residents of these areas. The Malay, Siamese, and Indonesians, for example, came to regard the Chinese as economically oppressive and exploitative, while the white rulers of these areas, especially in Australia and New Zealand, regarded them with suspicion for political and racial reasons. Among the causes of this political suspicion were that emigrant Chinese remained loyal to their families at home and to the homeland itself, that they were generally excluded from citizenship in areas to which they emigrated, and that they continued to be regarded as citizens by successive Chinese governments. The loyalty of emigrant Chinese to their families at home became an important source of economic strength to these families and to China itself, because emigrant Chinese sent very large savings back to their families.

We have already mentioned the important role played by peasant handicrafts in traditional Chinese society. It would, perhaps, not be any real exaggeration to say that peasant handicrafts were the factor which permitted the traditional form of society to continue, not only in China but in all of Asia. This society was based on an inefficient agricultural system in which the political, military, legal, and economic claims of the upper classes drained from the peasantry such a large proportion of their agricultural produce that the peasant was kept pressed down to the subsistence level (and, in much of China, below this level). Only by this process could Asia support its large urban populations and its large numbers of rulers, soldiers, bureaucrats, traders, priests, and scholars (none of whom produced the food, clothing, or shelter they were consuming). In all Asiatic countries the peasants on the land were underemployed in agricultural activities, because of the seasonal nature of their work. In the course of time there had grown up a solution to this social-agrarian problem: in their spare time the peasantry occupied themselves with handicrafts and other nonagricultural activities and then sold the products of their labor to the cities for money to be used to buy necessities. In real terms this meant that the agricultural products which were flowing from the peasantry to the upper classes (and generally from rural areas to the cities) were replaced in part by handicrafts, leaving a somewhat larger share of the peasants' agricultural products in the hands of peasants. It was this arrangement which made it possible for the Chinese peasantry to raise their incomes up to the subsistence level.

The importance of this relationship should be obvious. If it were destroyed, the peasant would be faced with a cruel alternative: either he could perish by falling below the subsistence level or he could turn to violence in order to reduce the claims which the upper classes had on his agricultural products. In the long run every peasant group was driven toward the second of these alternatives. As a result, all Asia by 1940 was in the grip of a profound political and social upheaval because, a generation earlier the demand for the products of peasants' handicrafts had been reduced.

The destruction of this delicately balanced system occurred when cheap, machine-made products of Western manufacture began to flow into Asiatic countries. Native products such as textiles, metal goods, paper, wood carvings, pottery, hats, baskets, and such found it increasingly difficult to compete with Western manufactures in the markets of their own cities. As a result, the peasantry found it increasingly difficult to shift the legal and economic claims which the upper, urban, classes held against them from agricultural products to handicraft products. And, as a consequence of this, the percentage of their agricultural products which was being taken from the peasantry by the claims of other classes began to rise.

This destruction of the local market for native handicrafts could have been prevented if high customs duties had been imposed on European industrial goods. But one point on which the European Powers were agreed was that they would not allow "backward" countries to exclude their products with tariffs. In India, Indonesia, and some of the lesser states of southeastern Asia this was prevented by the European Powers taking over the government of the areas; in China, Egypt, Turkey, Persia, and some Malay states the European Powers took over no more than the financial system or the customs service. As a result, countries like China, Japan, and Turkey had to sign treaties maintaining their tariffs at 5 or 8 percent and allowing Europeans to control these services. Sir Robert Hart was head of the Chinese customs from 1863 to 1906, just as Sir Evelyn Baring (Lord Cromer) was head of the Egyptian financial system from 1879 to 1907, and Sir Edgar Vincent (Lord D'Abernon) was the chief figure in the Turkish financial system from 1882 to 1897.

As a consequence of the factors we have described, the position of the Chinese peasant was desperate by 1900, and became steadily worse. A moderate estimate (published in 1940) showed that lo percent of the farm population owned 53 percent of the cultivated land, while the other go percent had only 47 percent of the land. The majority of Chinese farmers had to rent at least some land, for which they paid, as rent, from one-third to one-half of the crop. Since their incomes were not adequate, more than half of all Chinese farmers had to borrow each year. On borrowed grain the interest rate was 85 percent a year; on money loans the interest rate was variable, being over 20 percent a year on nine-tenths of all loans made and over so percent a year on one-eighth of the loans made. Under such conditions of landownership, rental rates, and interest charges, the future was hopeless for the majority of Chinese farmers long before 1940. Yet the social revolution in China did not come until after 1940.

The slow growth of the social revolution in China was the result of many influences. Chinese population pressure was relieved to some extent in the last half of the nineteenth century by the famines of 1877-1879 (which killed about 12 million people), by the political disturbances of the Tai-Ping and other rebellions in 1848-1875 (which depopulated large areas), and by the continued high death rate. The continued influence of traditional ideas, especially Confucianism and respect for ancestral ways, held the lid on this boiling pot until this influence was destroyed in the period after 1900. Hope that some solution might be found by the republican regime after the collapse of the imperial regime in 1911 had a similar effect. And, lastly, the distribution of European weapons in Chinese society was such as to hinder rather than to assist revolution until well into the twentieth century. Then this distribution turned in a direction quite different from that in Western civilization. These last three points are sufficiently important to warrant a closer examination.

We have already mentioned that effective weapons which are difficult to use or expensive to obtain encourage the development of authoritarian regimes in any society. In the late medieval period, in Asia, cavalry provided such a weapon. Since the most effective cavalry was that of the pastoral Ural-Altaic-speaking peoples of central Asia, these peoples were able to conquer the peasant peoples of Russia, of Anatolia, of India, and of China. In the course of time, the alien regimes of three of these areas (not in Russia) were able to strengthen their authority by the acquisition of effective, and expensive, artillery. In Russia, the princes of Moscow, having been the agents of the Mongols, replaced them by becoming their imitators, and made the same transition to a mercenary army, based on cavalry and artillery, as the backbone of the ruling despotism. In Western civilization similar despotisms, but based on infantry and artillery, were controlled by figures like Louis XIV, Frederick the Great, or Gustavus Adolphus. In Western Civilization, however, the Agricultural Revolution after 1725 raised standards of living, while the Industrial Revolution after 1800 so lowered the cost of firearms that the ordinary citizen of western Europe and of North America could acquire the most effective weapon existing (the musket). As a result of this, and other factors, democracy came to these areas, along with mass armies of citizen-soldiers. In central and southern Europe where the Agricultural and Industrial revolutions came late or not at all, the victory of democracy was also late and incomplete.

In Asia generally, the revolution in weapons (meaning muskets and later rifles) came before the Agricultural Revolution or the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, most firearms were not locally made, but were imported and, being imported, came into the possession of the upper class of rulers, bureaucrats, and landlords and not into the hands of peasants or city masses. As a result, these ruling groups were generally able to maintain their position against their own masses even when they could not defend themselves against European Powers. As a consequence of this, any hope of partial reform or of a successful revolution early enough to be a moderate revolution became quite unlikely. In Russia and in Turkey it required defeat in a foreign war with European states to destroy the corrupt imperial regimes (1917-1921). Earlier, the czar had been able to crush the revolt of 1905, because the army remained loyal to the regime, while the sultan, in 1908, had to yield to a reform movement because it was supported by the army. In India, Malaya, and Indonesia the disarmed native peoples offered no threat of revolt to the ruling European Powers before 1940. In Japan the army, as we shall see, remained loyal to the regime and was able to dominate events so that no revolution was conceivable before 1940. But in China the trend of events was much more complex.

In China the people could not get weapons because of their low standards of living and the high cost of imported arms. As a result, power remained in the hands of the army, except for small groups who were financed by emigrant Chinese with relatively high incomes overseas. By 1911 the prestige of the imperial regime had fallen so low that it obtained support from almost no one, and the army refused to sustain it. As a result, the revolutionaries, supported by overseas money, were able to overthrow the imperial regime in an almost bloodless revolution, but were not able to control the army after they had technically come to power. The army, leaving the politicians to squabble over forms of government or areas of jurisdiction, became independent political powers loyal to their own chiefs ("warlords"), and supported themselves and maintained their supply of imported arms by exploiting the peasantry of the provinces. The result was a period of "warlordism" from 1920 to 1941.

In this period the Republican government was in nominal control of the whole country but was actually in control only of the seacoast and river valleys, chiefly in the south, while various warlords, operating as bandits, were in control of the interior and most of the north. In order to restore its control to the whole country, the Republican regime needed money and imported arms. Accordingly, it tried two expedients in sequence. The first expedient, in the period 1920-1927, sought to restore its power in China by obtaining financial and military support from foreign countries (Western countries, Japan, or Soviet Russia). This expedient failed, either because these foreign Powers were unwilling to assist or (in the case of Japan and Soviet Russia) were willing to help only on terms which would have ended China's independent political status. As a consequence, after 1927, the Republican regime underwent a profound change, shifting from a democratic to an authoritarian organization, changing its name from Republican to Nationalist, and seeking the money and arms to restore its control over the country by making an alliance with the landlord, commercial, and banking classes of the eastern Chinese cities. These propertied classes could provide the Republican regime with the money to obtain foreign arms in order to fight the warlords of the west and north, but these groups would not support any Republican effort to deal with the social and economic problems facing the great mass of the Chinese peoples.

While the Republican armies and the warlords were struggling with each other over the prostrate backs of the Chinese masses, the Japanese attacked China in 1931 and 1937. In order to resist the Japanese it became necessary, after 1940, to arm the Chinese masses. This arming of the masses of Chinese in order to defeat Japan in 1941-1945 made it impossible to continue the Republican regime after 1945 so long as it continued to be allied with the upper economic and social groups of China, since the masses regarded these groups as exploiters. At the same time, changes to more expensive and more complex weapons made it impossible either for warlordism to revive or for the Chinese masses to use their weapons to establish a democratic regime. The new weapons, like airplanes and tanks, could not be supported by peasants on a provincial basis nor could they be operated by peasants. The former fact ended warlordism, while the latter fact ended any possibility of democracy. In view of the low productivity of Chinese agriculture and the difficulty of accumulating sufficient capital either to buy or to manufacture such expensive weapons, these weapons (in either way) could be acquired only by a government in control of most of China and could be used only by a professional army loyal to that government. Under such conditions it was to be expected that such a government would be authoritarian and would continue to exploit the peasantry (in order to accumulate capital either to buy such weapons abroad or to industrialize enough to make them at home, or both).

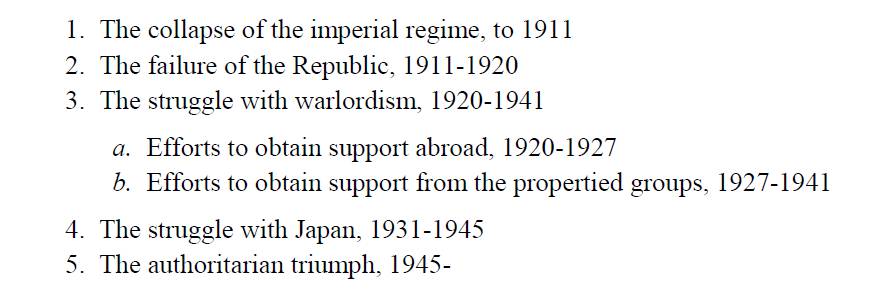

From this point of view the history of China in the twentieth century presents five phases, as follows:

The collapse of the imperial regime has already been discussed as a political and economic development. It was also an ideological development. The authoritarian and traditionalist ideology of the old China, in which social conservatism, Confucianist philosophy, and ancestor worship were intimately blended together, was well fitted to resist the intrusion of new ideas and new patterns of action. The failure of the imperial regime to resist the military, economic, and political penetration of Western Civilization gave a fatal blow to this ideology. New ideas of Western origin were introduced, at first by Christian missionaries and later by Chinese students who had studied abroad. By 1900 there were thousands of such students. They had acquired Western ideas which were completely incompatible with the older Chinese system. In general, such Western ideas were not traditionalist or authoritarian, and were, thus, destructive to the Chinese patriarchal family, to ancestor worship, or to the imperial autocracy. The students brought back from abroad Western ideas of science, of democracy, of parliamentarianism, of empiricism, of self-reliance, of liberalism, of individualism, and of pragmatism. Their possession of such ideas made it impossible for them to fit into their own country. As a result, they attempted to change it, developing a revolutionary fervor which merged with the anti-dynastic secret societies which had existed in China since the Manchus took over the country in 1644.

Japan's victory over China in 1894-1895 in a war arising from a dispute over Korea, and especially the Japanese victory over Russia in the war of 1904-1905, gave a great impetus to the revolutionary spirit in China because these events seemed to show that an Oriental country could adopt Western techniques successfully. The failure of the Boxer movement in 1900 to expel Westerners without using such Western techniques also increased the revolutionary fervor in China. As a consequence of such events, the supporters of the imperial regime began to lose faith in their own system and in their own ideology. They began to install piecemeal, hesitant, and ineffective reforms which disrupted the imperial system without in any way strengthening it. Marriage between Manchu and Chinese was sanctioned for the first time (1902); Manchuria was opened to settlement by Chinese (1907); the system of imperial examinations based on the old literary scholarship for admission to the civil service and the mandarinate were abolished and a Ministry of Education, copied from Japan, was established (1905); a drafted constitution was published providing for provincial assemblies and a future national parliament (1908); the law was codified (1910).

These concessions did not strengthen the imperial regime, but merely intensified the revolutionary feeling. The death of the emperor and of Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi, who had been the real ruler of the country (1908), brought to the throne a two-year-old child, P'u-I. The reactionary elements made use of the regency to obstruct reform, dismissing the conservative reform minister Y"uan Shih-k’ai (1859-1916). Discovery of the headquarters of the revolutionists at Hankow in 1911 precipitated the revolution. While Dr. Sun Yat-sen (1866-1925) hurried back to China from abroad, whence he had directed the revolutionary movement for many years, the tottering imperial regime recalled Yuan Shih-K'ai to take command of the anti-revolutionary armies. Instead he cooperated with the revolutionists, forced the abdication of the Manchu dynasty, and plotted to have himself elected as president of the Chinese Republic. Sun Yat-sen who had already been elected provisional president by the National Assembly at Nanking, accepted this situation, retiring from office, and calling on all Chinese to support President Y"uan.

The contrast between Dr. Sun and General Y"uan, the first and second presidents of the Chinese Republic, was as sharp as could be. Dr. Sun was a believer in Western ideas, especially in science, democracy, parliamentary government, and socialism, and had lived for most of his life as an exile overseas. He was self-sacrificing, idealistic, and somewhat impractical. General Y"uan, on the other hand, was purely Chinese, a product of the imperial bureaucracy, who had no knowledge of Western ideas and no faith in either democracy or parliamentary government. He was vigorous, corrupt, realistic, and ambitious. The real basis of his power rested in the new westernized army which he had built up as governor-general of Chihli in 1901-1907. In this force there were five divisions, well trained and completely loyal to Y"uan. The officers of these units had been picked and trained by Yuan, and played principal roles in Chinese politics after 1916.

As president, Y"uan opposed almost everything for which Dr. Sun had dreamed. He expanded the army, bribed politicians, and eliminated those who could not be bribed. The chief support of his policies came from a lb25 million loan from Britain, France, Russia, and Japan in 1913. This made him independent of the assembly and of Dr. Sun's political party, the Kuomintang, which dominated the assembly. In 1913 one element of Sun's followers revolted against Y"uan but were crushed. Y"uan dissolved the Kuomintang, arrested its members, dismissed the Parliament, and revised the constitution to give himself dictatorial powers as president for life, with the right to name his own successor. He was arranging to have himself proclaimed emperor when he died m 1916.

As soon as Y"uan died, the military leaders stationed in various parts of the country began to consolidate their power on a local basis. One of them even restored the Manchu dynasty, but it was removed again within two weeks. By the end of 1916 China was under the nominal rule of two governments, one at Peking under Feng Kuo-chang (one of Yuan's militarists) and a secession government at Canton under Dr. Sun. Both of these functioned under a series of fluctuating paper constitutions, but the real power of both was based on the loyalty of local armies. Because in both cases the armies of more remote areas were semi-independent, government in those areas was a matter of negotiation rather than of commands from the capital. Even Dr. Sun saw this situation sufficiently clearly to organize the Cantonese government as a military system with himself as generalissimo (1917). Dr. Sun was so unfitted for this military post that on two occasions he had to flee from his own generals to security in the French concession at Shanghai (1918-1922). Under such conditions Dr. Sun was unable to achieve any of his pet schemes, such as the vigorous political education of the Chinese people, a widespread network of Chinese railways built with foreign capital, or the industrialization of China on a socialist basis. Instead, by 1920, warlordism was supreme, and the Westernized Chinese found opportunity to exercise their new knowledge only in education and in the diplomatic service. Within China itself, command of a well-drilled army in control of a compact group of local provinces was far more valuable than any Westernized knowledge acquired as a student abroad.

THE RESURGENCE OF JAPAN TO 1918

The history of Japan in the twentieth century is quite distinct from that of the other Asiatic peoples. Among the latter the impact of the West led to the disruption of the social and economic structure, the abandonment of the traditional ideologies, and the revelation of the weakness of native political and military systems. In Japan these events either did not occur or occurred in a quite different fashion. Until 1945 Japan's political and military systems were strengthened by Western influences; the older Japanese ideology was retained, relatively intact, even by those who were most energetic copiers of Western ways; and the changes in the older social and economic structure were kept within manageable limits and were directed in a progressive direction. The real reason for these differences probably rests in the ideological factor – that the Japanese, even the vigorous Westernizers, retained the old Japanese point of view and, as a consequence, were allied with the older Japanese political, economic, and social structure rather than opposed to it (as, for example, Westernizers were in India, in China, or in Turkey). The ability of the Japanese to westernize without going into opposition to the basic core of the older system gave a degree of discipline and a sense of unquestioning direction to their lives which allowed Japan to achieve a phenomenal amount of westernization without weakening the older structure or without disrupting it. In a sense until about 1950, Japan took from Western culture only superficial and material details in an imitative way and amalgamated these newly acquired items around the older ideological, political, military, and social structure to make it more powerful and effective. The essential item which the Japanese retained from their traditional society and did not adopt from Western civilization was the ideology. In time, as we shall see, this was very dangerous to both of the societies concerned, to Japan and to the West.

Originally Japan came into contact with Western civilization in the sixteenth century, about as early as any other Asiatic peoples, but, within a hundred years, Japan was able to eject the West, to exterminate most of its Christian converts, and to slam its doors against the entrance of any Western influences. A very limited amount of trade was permitted on a restricted basis, but only with the Dutch and only through the single port of Nagasaki.

Japan Is Dominated by the Tokugawa Family

Japan, thus isolated from the world, was dominated by the military dictatorship (or shogunate) of the Tokugawa family. The imperial family had been retired to a largely religious seclusion whence it reigned but did not rule. Beneath the shogun the country was organized in a hereditary hierarchy, headed by local feudal lords. Beneath these lords there were, in descending ranks, armed retainers (samurai), peasants, artisans, and merchants. The whole system was, in theory at least, rigid and unchanging, being based on the double justification of blood and of religion. This was in obvious and sharp contrast with the social organization of China, which was based, in theory, on virtue and on educational training. In Japan virtue and ability were considered to be hereditary rather than acquired characteristics, and, accordingly, each social class had innate differences which had to be maintained by restrictions on intermarriage. The emperor was of the highest level, being descended from the supreme sun goddess, while the lesser lords were descended from lesser gods of varying degrees of remoteness from the sun goddess. Such a point of view discouraged all revolution or social change and all "circulation of the elites," with the result that China's multiplicity of dynasties and rise and fall of families was matched in Japan by a single dynasty whose origins ran back into the remote past, while the dominant individuals of Japanese public life in the twentieth century were members of the same families and clans which were dominating Japanese life centuries ago.

All Non-Japanese Are Basically Inferior Beings

From this basic idea flowed a number of beliefs which continued to be accepted by most Japanese almost to the present. Most fundamental was the belief that all Japanese were members of a single breed consisting of many different branches or clans of superior or inferior status, depending on their degree of relationship to the imperial family. The individual was of no real significance, while the families and the breed were of major significance, for individuals lived but briefly and possessed little beyond what they received from their ancestors to pass on to their descendants. In this fashion it was accepted by all Japanese that society was more important than any individual and could demand any sacrifice from him, that men were by nature unequal and should be prepared to serve loyally in the particular status into which each had been born, that society is nothing but a great patriarchal system, that in this system authority is based on the personal superiority of man over man and not on any rule of law, that, accordingly, all law is little more than some temporary order from some superior being, and that all non-Japanese, lacking divine ancestry, are basically inferior beings, existing only one cut above the level of animals and, accordingly, having no basis on which to claim any consideration, loyalty, or consistency of treatment at the hands of Japanese.

Japanese World View Is Anti-thetical to Christian World View

This Japanese ideology was as anti-thetical to the outlook of the Christian West as any which the West encountered in its contacts with other civilizations. It was also an ideology which was peculiarly fitted to resist the intrusion of Western ideas. As a result, Japan was able to accept and to incorporate into its way of life all kinds of Western techniques and material culture without disorganizing its own outlook or its own basic social structure.

The Tokugawa Shogunate was already long past its prime when, in 1853, the "black ships" of Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Tokyo Bay. That these vessels could move against the wind, and carried guns more powerful than any the Japanese had ever imagined, was a great shock to the natives of Nippon. The feudal lords who had been growing restive under Tokugawa rule used this event as an excuse to end that rule. These lords, especially the representatives of four western clans, demanded that the emergency be met by abolishing the shogunate and restoring all authority to the hands of the emperor. For more than a decade the decision whether to open Japan to the West or to try to continue the policy of exclusion hung in the balance. In 1863-1866 a series of naval demonstrations and bombardments of Japanese ports by Western Powers forced the opening of Japan and imposed on the country a tariff agreement which restricted import duties to 5 percent until 1899. A new and vigorous emperor came to the throne and accepted the resignation of the last shogun (1867). Japan at once embarked on a policy of rapid Westernization.

Shift in Power from the Shogun to Four Western Japanese Clans

The period in Japanese history from the so-called Meiji Restoration of 1867 to the granting of a constitution in 1889 is of the most vital importance. In theory what had occurred had been a restoration of Japan's rule from the hands of the shogun back into the hands of the emperor. In fact what occurred was a shift in power from the shogun to the leaders of four western Japanese clans who proceeded to rule Japan in the emperor's name and from the emperor's shadow. These four clans of Satsuma, Choshu, Hizen, and Tosa won the support of certain nobles of the imperial court (such as Saionji and Konoe) and of the richer mercantile families (such as Mitsui) and were able to overthrow the shogun, crush his supporters (in the Battle of Uemo in 1868), and win control of the government and of the emperor himself. The emperor did not assume control of the government, but remained in a semi-religious seclusion, too exalted to concern himself with the functioning of the governmental system except in critical emergencies. In such emergencies the emperor generally did no more than issue a statement or order ("imperial rescript") which had been drawn up by the leaders of the Restoration.

The Meiji Oligarchy

These leaders, organized in a shadowy group known as the Meiji oligarchy, had obtained complete domination of Japan by 1889. To cover this fact with camouflage, they unleashed a vigorous propaganda of revived Shintoism and of abject submission to the emperor which culminated in the extreme emperor worship of 1941-1945. To provide an administrative basis for their rule, the oligarchy created an extensive governmental bureaucracy recruited from their supporters and inferior members. To provide an economic basis for their rule, this oligarchy used their political influence to pay themselves extensive pensions and governmental grants (presumably as compensation for the ending of their feudal incomes) and to engage in corrupt business relationships with their allies in the commercial classes (like Mitsui or Mitsubishi). To provide a military basis for their rule, the oligarchy created a new imperial army and navy and penetrated the upper ranks of these so that they were able to dominate these forces as they dominated the civil bureaucracy. To provide a social basis for their rule, the oligarchy created an entirely new peerage of five ranks of nobility recruited from their own members and supporters.

The Japanese Oligarchy Draw Up a Constitution That Would Conceal Their Political Domination of the Country

Having thus assured their dominant position in the administrative, economic, military, and social life of Japan, the oligarchy in 1889 drew up a constitution which would assure, and yet conceal, their political domination of the country. This constitution did not pretend to be a product of the Japanese people or of the Japanese nation; popular sovereignty and democracy had no place in it. Instead this constitution pretended to be an emission from the emperor, setting up a system in which all government would be in his name, and all officials would be personally responsible to him. It provided for a bicameral Diet as a legislature. The House of Peers consisted of the new nobility which had been created in 1884, while the House of Representatives was to be elected "according to the law." All legislation had to pass each house by majority vote and be signed by a minister of state.

These ministers, established as a Council of State in 1885, were responsible to the emperor and not to the Diet. Their tasks were carried out through the bureaucracy which was already established. All money appropriations, like other laws, had to obtain the assent of the Diet, but, if the budget was not accepted by this body, the budget of the preceding year was repeated automatically for the following year. The emperor had extensive powers to issue ordinances which had the force of law and required a minister's signature, as did other laws.

Japanese Constitution Based upon the Constitution of Imperial Germany

This constitution of 1889 was based on the constitution of Imperial Germany and was forced on Japan by the Meiji oligarchy in order to circumvent and anticipate any future agitation for a more liberal constitution based on British, American, or French models. Basically, the form and functioning of the constitution was of little significance, for the country continued to be run by the Meiji oligarchy through their domination of the army and navy, the bureaucracy, economic and social life, and the opinion-forming agencies such as education and religion. In political life this oligarchy was able to control the emperor, the Privy Council, the House of Peers, the judiciary, and the bureaucracy.

The Oligarchy's Chief Aim Was to Westernize Japan

This left only one possible organ of government, the Diet, through which the oligarchy might be challenged. Moreover, the Diet had only one means (its right to pass the annual budget) by which it could strike back at the oligarchy. This right was of little significance so long as the oligarchy did not want to increase the budget, since the budget of the previous year would be repeated if the Diet rejected the budget of the following year. However, the oligarchy could not be satisfied with a repetition of an earlier budget, for the oligarchy's chief aim, after they had ensured their own wealth and power, was to westernize Japan rapidly enough to be able to defend it against the pressure of the Great Powers of the West.

Controlling the Elections to the Diet

All these things required a constantly growing budget, and thus gave the Diet a more important role than it would otherwise have had. This role, however, was more of a nuisance than a serious restriction on the power of the Meiji oligarchy because the power of the Diet could be overcome in various ways. Originally, the oligarchy planned to give the Imperial Household such a large endowment of property that its income would be sufficient to support the army and navy outside the national budget. This plan was abandoned as impractical, although the Imperial Household and all its rules were put outside the scope of the constitution. Accordingly, an alternative plan was adopted: to control the elections to the Diet so that its membership would be docile to the wishes of the Meiji oligarchy. As we shall see, controlling the elections to the Diet was possible, but ensuring its docility was quite a different matter.

The Meiji Oligarchy Controls the Police and the Government

The elections to the Diet could be controlled in three ways: by a restricted suffrage, by campaign contributions, and by bureaucratic manipulation of the elections and the returns. The suffrage was restricted for many years on a property basis, so that, in 1900, only one person in a hundred had the right to vote. The close alliance between the Meiji oligarchy and the richest members of the expanding economic system made it perfectly easy to control the flow of campaign contributions. And if these two methods failed, the Meiji oligarchy controlled both the police and the prefectural bureaucracy which supervised the elections and counted the returns. In case of need, they did not hesitate to use these instruments, censoring opposition papers, prohibiting opposition meetings, using violence, if necessary, to prevent opposition voting, and reporting, through the prefects, as elected candidates who had clearly failed to obtain the largest vote.

The Meiji Oligarchy Controls the Emperor

These methods were used from the beginning. In the first Diet of 1889, gangsters employed by the oligarchy prevented opposition members from entering the Diet chamber, and at least twenty-eight other members were bribed to shift their votes. In the elections of 189: violence was used, mostly in districts opposed to the government, so that 25 persons were killed and 388 were injured. The government still lost that election but continued to control the Cabinet. It even dismissed eleven prefectural governors who had been stealing votes, as much for their failure to steal enough as for their action in stealing any. When the resulting Diet refused to appropriate for an enlarged navy, it was sent home for eighteen days, and then reassembled to receive an imperial rescript which gave 1.8 million yen over a six-year period from the Imperial Household for the project and went on to order all public officials to contribute one-tenth of their salaries each year for the duration of the naval building program which the Diet had refused to finance. In this fashion, the Diet's control of increased appropriations was circumvented by the Meiji oligarchy's control of the emperor.

In view of the dominant position of the Meiji oligarchy in Japanese life from 1867 until after 1992, it would be a mistake to interpret such occurrences as unruly Diets, the growth of political parties, or even the establishment of adult manhood suffrage (in 1925) as such events would be interpreted in European history. In the West we are accustomed to narrations about heroic struggles for civil rights and individual liberties, or about the efforts of commercial and industrial capitalists to capture at least a share of political and social power from the hands of the landed aristocracy, the feudal nobility, or the Church. We are acquainted with movements by the masses for political democracy, and with agitations by peasants and workers for economic advantages. All these movements, which fill the pages of European history books, are either absent or have an entirely different significance in Japanese history.

Shintoism Was Promoted by the Meiji Oligarchy to Control the People

In Japan history presents a basic solidarity of outlook and of purpose, punctuated with brief conflicting outbursts which seem to be contradictory and inexplicable. The explanation of this is to be found in the fact that there was, indeed, a solidarity of outlook but that this solidarity was considerably less solid than it appeared, for, beneath it, Japanese society was filled with fissures and discontents. The solidarity of outlook rested on the ideology which we have mentioned. This ideology, sometimes called Shintoism, was propagated by the upper classes, especially by the Meiji oligarchy but was more sincerely embraced by the lower classes, especially by the rural masses, than it was by the oligarchy which propagated it. This ideology accepted an authoritarian, hierarchical, patriarchal society, based on families, clans, and nation, culminating in respect and subordination to the emperor. In this system there was no place for individualism, self-interest, human liberties, or civil rights.

Shintoism Allowed the Meiji Oligarchy to Pursue Policies of Self-Aggrandizement

In general, this system was accepted by the mass of the Japanese peoples. As a consequence, these masses allowed the oligarchy to pursue policies of selfish self-aggrandizement, of ruthless exploitation, and of revolutionary economic and social change with little resistance. The peasants were oppressed by universal military service, by high taxes and high interest rates, by low farm prices and high industrial prices, and by the destruction of the market for peasant handicrafts. They revolted briefly and locally in 1884-1885, but were crushed and never revolted again, although they continued to be exploited. All earlier legislation seeking to protect peasant proprietors or to prevent monopolization of the land was revoked in the 1870's.

In the 1880's there was a drastic reduction in the number of landowners, through heavy taxes, high interest rates, and low prices for farm products. At the same time the growth of urban industry began to destroy the market for peasant handicrafts and the rural "putting-out system" of manufacture. In seven years, 1883-1890, about 360,000 peasant proprietors were dispossessed of 5 million yen worth of land because of total tax arrears of only 114,178 yen (or arrears of only one-third yen, that is, 17 American cents, per person). In the same period, owners were dispossessed of about one hundred times as much land by foreclosure of mortgages. This process continued at varying rates, until, by 1940, three-quarters of Japanese peasants were tenants or part-tenants paying rents of at least half of their annual crop.

Pressures on Japanese Peasants

In spite of their acceptance of authority and Shinto ideology, the pressures on Japanese peasants would have reached the explosive point if safety valves had not been provided for them. Among these pressures we must take notice of that arising from population increase, a problem arising, as in most Asiatic countries, from the introduction of Western medicine and sanitation. Before the opening of Japan, its population had remained fairly stable at 28-30 million for several centuries. This stability arose from a high death rate supplemented by frequent famines and the practice of infanticide and abortion. By 1870 the population began to grow, rising from 30 million to 56 million in 1920, to 73 million in 1940, and reaching 87 million in 1955.

Meiji Oligarchy Controls Shipping, Railroads, Industry and Services

The safety valve in the Japanese peasant world resided in the fact that opportunities were opened, with increasing rapidity, in nonagricultural activities in the period 1870-1920. These nonagricultural activities were made available from the fact that the exploiting oligarchy used its own growing income to create such activities by investment in shipping, railroads, industry, and services. These activities made it possible to drain the growing peasant population from the rural areas into the cities. A law of 1873 which established primogeniture in the inheritance of peasant property made it evident that the rural population which migrated to the cities would be second and third sons rather than heads of families. This had numerous social and psychological results, of which the chief was that the new urban population consisted of men detached from the discipline of the patriarchal family and thus less under the influence of the general authoritarian Japanese psychology and more under the influence of demoralizing urban forces. As a consequence, this group, after 1920, became a challenge to the stability of Japanese society.

Exploitation of Japanese Society

In the cities the working masses of Japanese society continued to be exploited, but now by low wages rather than by high rents, taxes, or interest rates. These urban masses, like the rural masses whence they had been drawn, submitted to such exploitation without resistance for a much longer period than Europeans would have done because they continued to accept the authoritarian, submissive Shintoist ideology. They were excluded from participation in political life until the establishment of adult manhood suffrage in 1925. It was not until after this date that any noticeable weakening of the authoritarian Japanese ideology began to appear among the urban masses.

Resistance of the urban masses to exploitation through economic or social organizations was weakened by the restrictions on workers' organizations of all kinds. The general restrictions on the press, on assemblies, on freedom of speech, and on the establishment of "secret" societies were enforced quite strictly against all groups and doubly so against laboring groups. There were minor socialistic and laborers' agitations in the twenty years 1890-1910. These were brought to a violent end in 1910 by the execution of twelve persons for anarchistic agitations. The labor movement did not raise its head again until the economic crisis of 1919-1922.

The Low-Wage Policy of Japanese Originated in the Self-Interest of the Elite

The low-wage policy of the Japanese industrial system originated in the self-interest of the early capitalists, but came to be justified with the argument that the only commodity Japan had to offer the world, and the only one on which it would construct a status as a Great Power, was its large supply of cheap labor. Japan's mineral resources, including coal, iron, or petroleum, were poor in both quality and quantity; of textile raw materials it had only silk, and lacked both cotton and wool. It had no natural resources of importance for which there was world demand such as were to be found in the tin of Malaya, the rubber of Indonesia, or the cocoa of West Africa; it had neither the land nor the fodder to produce either dairy or animal products as Argentina, Denmark, New Zealand, or Australia. The only important resources it had which could be used to provide export goods to exchange for imported coal, iron, or oil were silk, forest products, and products of the sea. All these required a considerable expenditure of labor, and these products could be sold abroad only if prices were kept low by keeping wage rates down.

Since these products did not command sufficient foreign exchange to allow Japan to pay for the imports of coal, iron, and oil which a Great Power must have, Japan had to find some method by which it could export its labor and obtain pay for it. This led to the growth of manufacturing industries based on imported raw materials and the development of such service activities as fishing and ocean shipping. At an early date Japan began to develop an industrial system in which raw materials such as coal, wrought iron, raw cotton, or wool were imported, fabricated into more expensive and complex forms, and exported again for a higher price in the form of machinery or finished textiles. Other products which were exported included such forest products as tea, carved woods, or raw silk, or such products of Japanese labor as finished silks, canned fish, or shipping services.

The Meiji Oligarchy Is Controlled by a Small Group of Men

The political and economic decisions which led to these developments and which exploited the rural and urban masses of Japan were made by the Meiji oligarchy and their supporters. The decision-making powers in this oligarchy were concentrated in a surprisingly small group of men, in all, no more than a dozen in number, and made up, chiefly, of the leaders of the four western clans which had led the movement against the shogun in 1867. These leaders came in time to form a formal, if extralegal, group known as the Genro (or Council of Elder Statesmen). Of this group Robert Reischauer wrote in 1938: "It is these men who have been the real power behind the Throne. It became customary for their opinion to be asked and, more important still, to be followed in all matters of great significance to the welfare of the state. No Premier was ever appointed except from the recommendation of these men who became known as Genro. Until 1922 no important domestic legislation, no important foreign treaty escaped their perusal and sanction before it was signed by the Emperor. These men, in their time, were the actual rulers of Japan."

The Eight Members of the Genro Control Japan

The importance of this group can be seen from the fact that the Genro had only eight members, yet the office of prime minister was held by a Genro from 1885 to 1916, and the important post of president of the Privy Council was held by a Genro from its creation in 1889 to 1922 (except for the years 1890-1892 when Count Oki of the Hizen clan held it for Okuma). If we list the eight Genro with three of their close associates, we shall be setting down the chief personnel of Japanese history in the period covered by this chapter. To such a list we might add certain other significant facts, such as the social origins of these men, the dates of their deaths, and their dominant connections with the two branches of the defense forces and with the two greatest Japanese industrial monopolies. The significance of these connections will appear in a moment.

The Unofficial Rulers of Japan

Japanese history from 1890 to 1940 is largely a commentary on this table. We have said that the Meiji Restoration of 1868 resulted from an alliance of four western clans and some court nobles against the shogunate and that this alliance was financed by commercial groups led by Mitsui. The leaders of this movement who were still alive after 1890 came to form the Genro, the real but unofficial rulers of Japan. As the years passed and the Genro became older and died, their power became weaker, and there arose two claimants to succeed them: the militarists and the political parties. In this struggle the social groups behind the political parties were so diverse and so corrupt that their success was never in the realm of practical politics. In spite of this fact, the struggle between the militarists and the political parties looked fairly even until 1935, not because of any strength or natural ability in the ranks of the latter but simply because Saionji, the "Last of the Genro" and the only non-clan member in that select group, did all he could to delay or to avoid the almost inevitable triumph of the militarists.

All the factors in this struggle and the political events of Japanese history arising from the interplay of these factors go back to their roots in the Genro as it existed before 1900. The political parties and Mitsubishi were built up as Hizen-Tosa weapons to combat the Choshu-Satsuma domination of the power nexus organized on the civilian-military bureaucracy allied with Mitsui; the army-navy rivalry (which appeared in 1912 and became acute after 1931) had its roots in an old competition between Choshu and Satsuma within the Genro; while the civilian-militarist struggle went back to the personal rivalry between Ito and Yamagata before 1900. Yet, in spite of these fissures and rivalries, the oligarchy as a whole generally presented a united front against outside groups (such as peasants, workers, intellectuals, or Christians) in Japan itself or against non-Japanese.

Ito – the Most Powerful Man in Japan

From 1882 to 1898 Ito was the dominant figure in the Meiji oligarchy, and the most powerful figure in Japan. As minister of the Imperial Household, he was charged with the task of drawing up the constitution of 1889; as president of the Privy Council, he guided the deliberations of the assembly which ratified this constitution; and as first prime minister of the new Japan, he established the foundations on which it would operate. In the process he entrenched the Sat-Cho oligarchy so firmly in power that the supporters of Tosa and Hizen began to agitate against the government, seeking to obtain what they regarded as their proper share of the plums of office.

Political Parties Arise in Japan

In order to build up opposition to the government, they organized the first real political parties, the Liberal Party of Itagaki (1881) and the Progressive Party of Okuma (1882). These parties adopted liberal and popular ideologies from bourgeois Europe, but, generally, these were not sincerely held or clearly understood. The real aim of these two groups was to make themselves so much of a nuisance to the prevailing oligarchy that they could obtain, as a price for relaxing their attacks, a share of the patronage of public office and of government contracts. Accordingly, the leaders of these parties, again and again, sold out their party followers in return for these concessions, generally dissolving their parties, to re-create them at some later date when their discontent with the prevailing oligarchy had risen once again. As a result, the opposition parties vanished and reappeared, and their leaders moved into and out of public office in accordance with the whims of satisfied or discontented personal ambitions.

The Great Monopolies of Japan

Just as Mitsui became the greatest industrial monopoly of Japan on the basis of its political connections with the prevalent Sat-Cho oligarchy, so Mitsubishi became Japan's second greatest monopoly on the basis of its political connections with the opposition groups of Tosa-Hizen. Indeed, Mitsubishi began its career as the commercial firm of the Tosa clan, and Y. Iwasaki, who had managed it in the latter role, continued to manage it when it blossomed into Mitsubishi. Both of these firms, and a handful of other monopolistic organizations which grew up later, were completely dependent for their profits and growth on political connections.

The Rise of the Zaibatsu